Numerical Aperture

In this article series we will go through the main specifications of microscope objectives. You will learn what all those numbers that you probably never really paid attention to actually mean, and how that can help you choose the best objectives for your needs.

Let's start with numerical aperture. This value is always engraved on microscope objectives (Fig. 1), and for good reason: this is one of the most important specifications as it effectively determines the objective resolution.

So, in this article, we will explain what the numerical aperture is and why it determines the resolution of your microscopy images. We will start with a rather oversimplified explanation and then we will do a deep dive into the physics behind it.

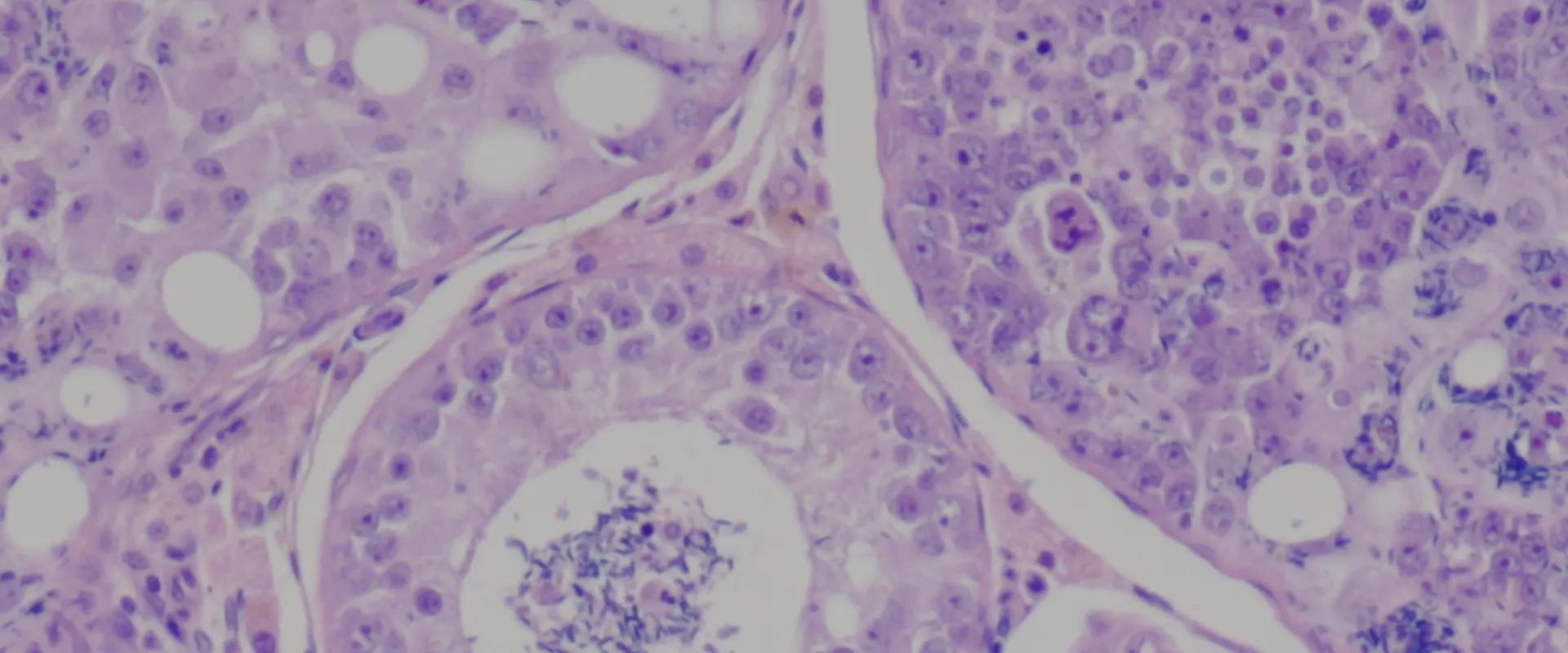

Fig. 1: Here we can see two 100x oil immersion objectives. On the left, we have a standard (achromatic) objective with a numerical aperture of 1.25. On the right is a highly corrected objective with a much higher numerical aperture: 1.49. This NA is at the very edge of what is physically possible to achieve using oil immersion. Due to this extremely high aperture, the objective on the right also features two correction collars to correct for spherical optical aberrations, which are critical to manage at such high numerical apertures.

In simple words, the numerical aperture is the amount of information an objective can capture from a specimen. That directly relates to the amount of light it can capture, but also to its resolving power (figure 2). The physics behind that is more complex, and before we put in the effort of explaining it, we first want to convince you with examples that a higher numerical aperture really does give higher resolution.

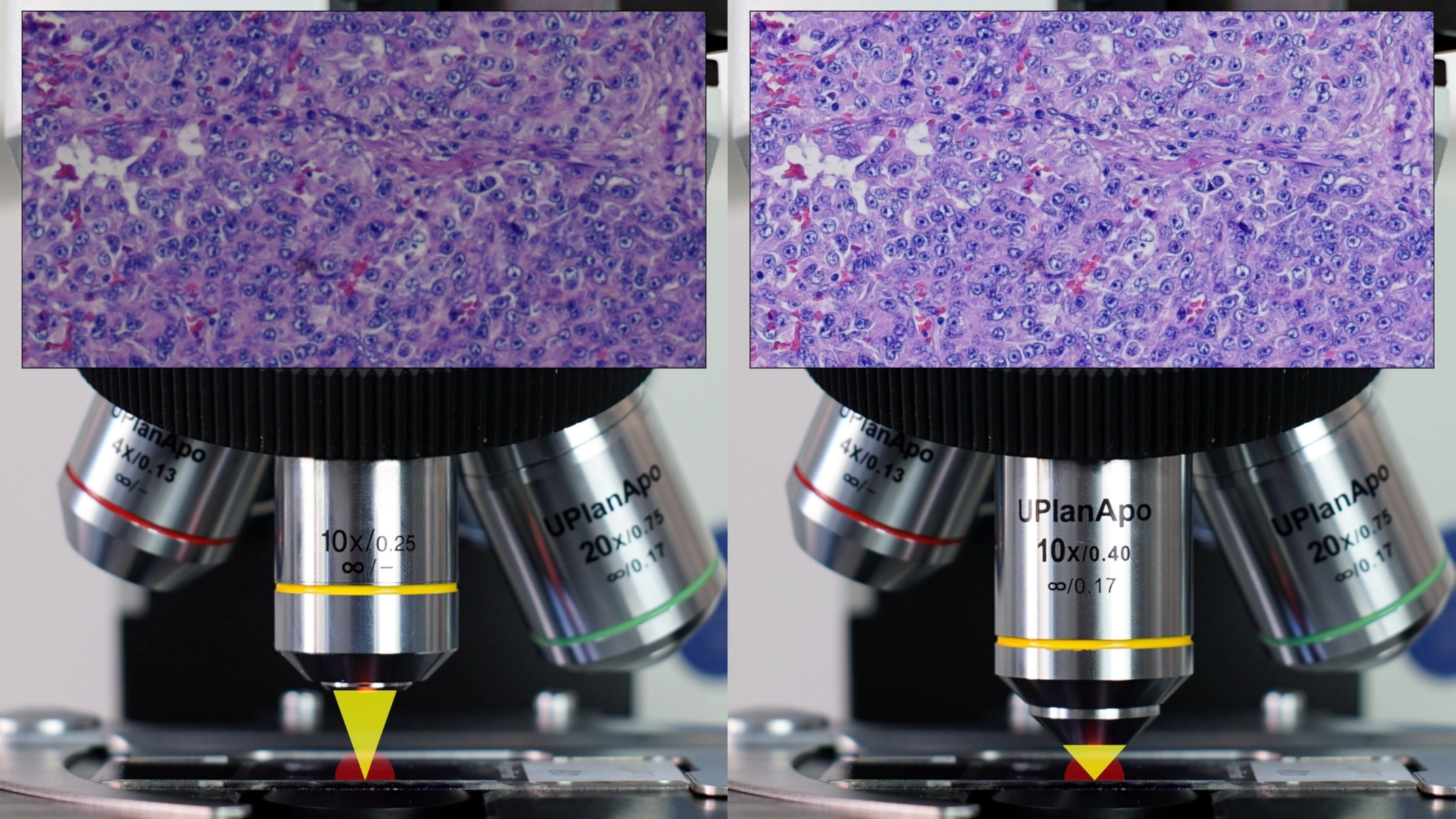

Fig. 2: This image illustrates the concept of numerical aperture. The 10x objective on the left has a low NA; it can only gather light from a narrow angle, or "cone." The 10x objective on the right has a much higher NA, allowing it to capture light from a much wider cone. With wider cone the objective is not only capturing more light, but also more information (higher-order diffraction patterns) from the specimen, which is the key to higher resolution.

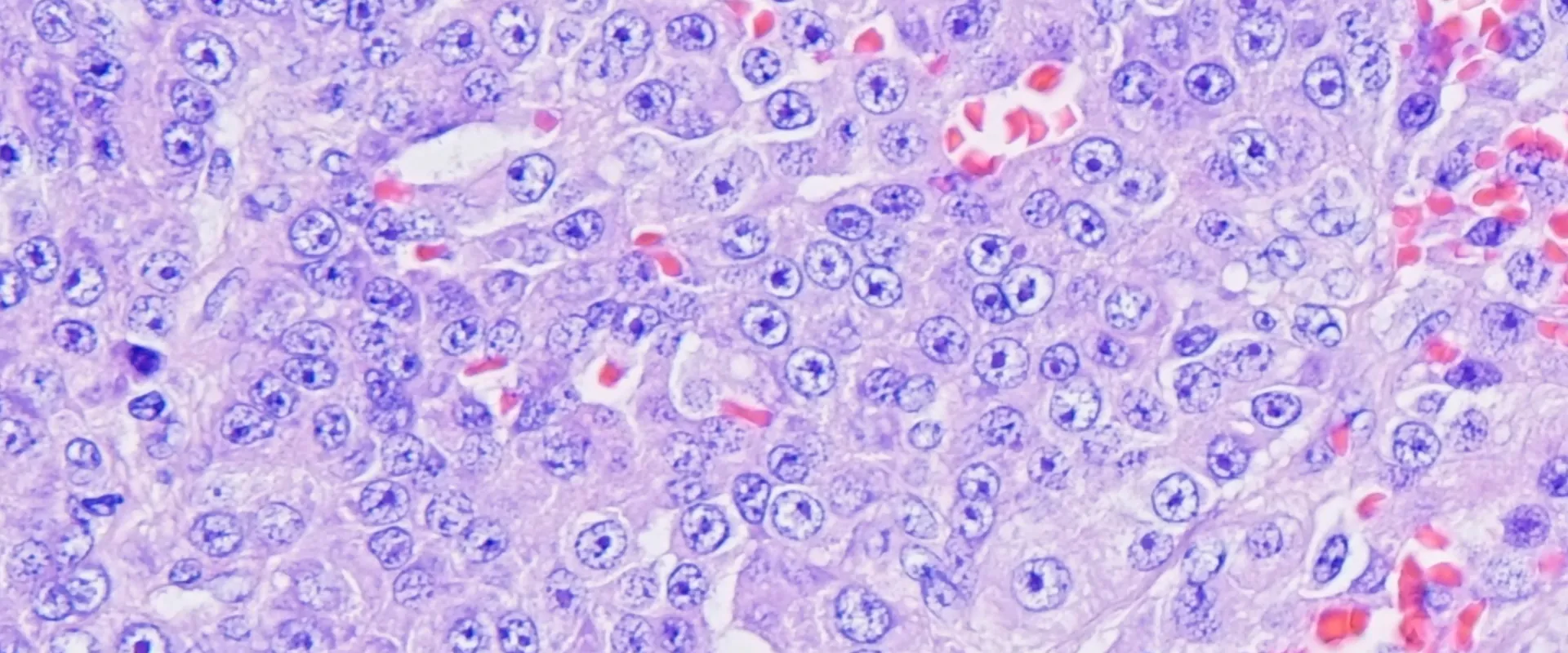

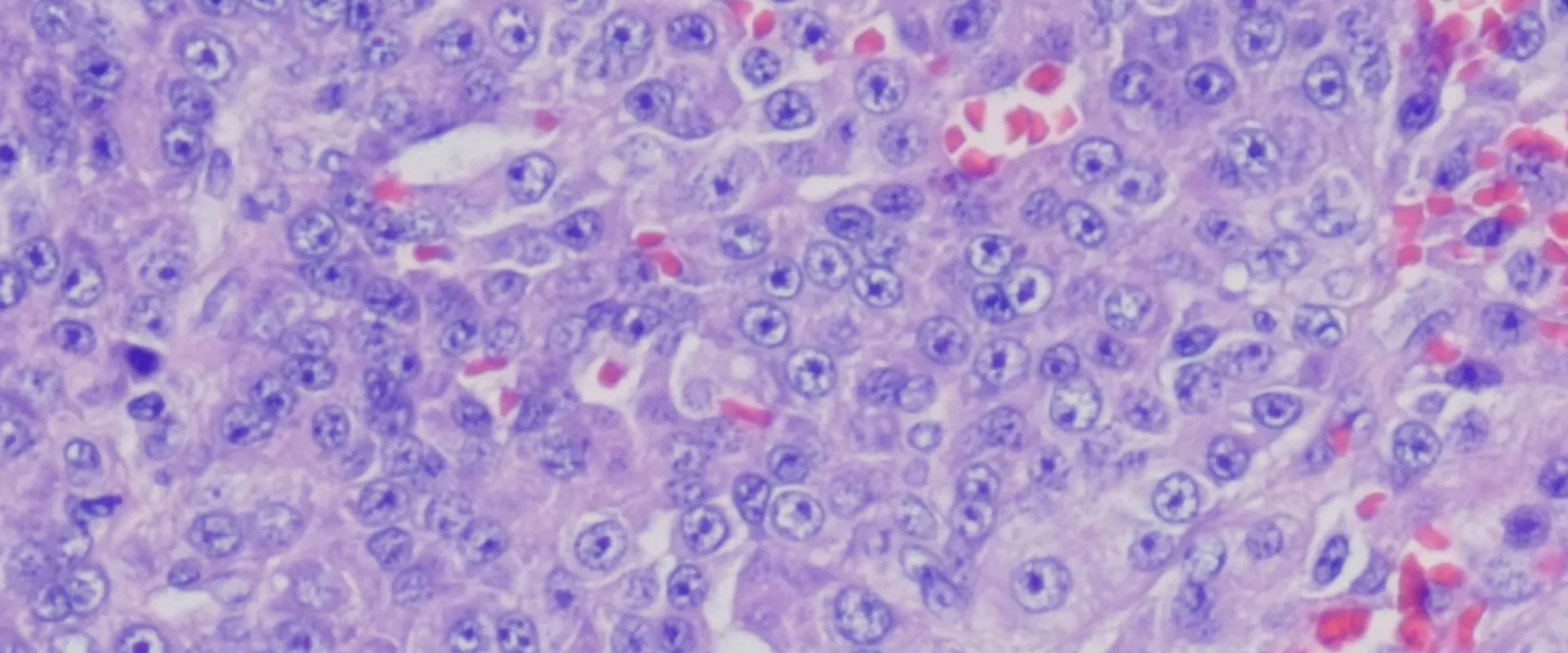

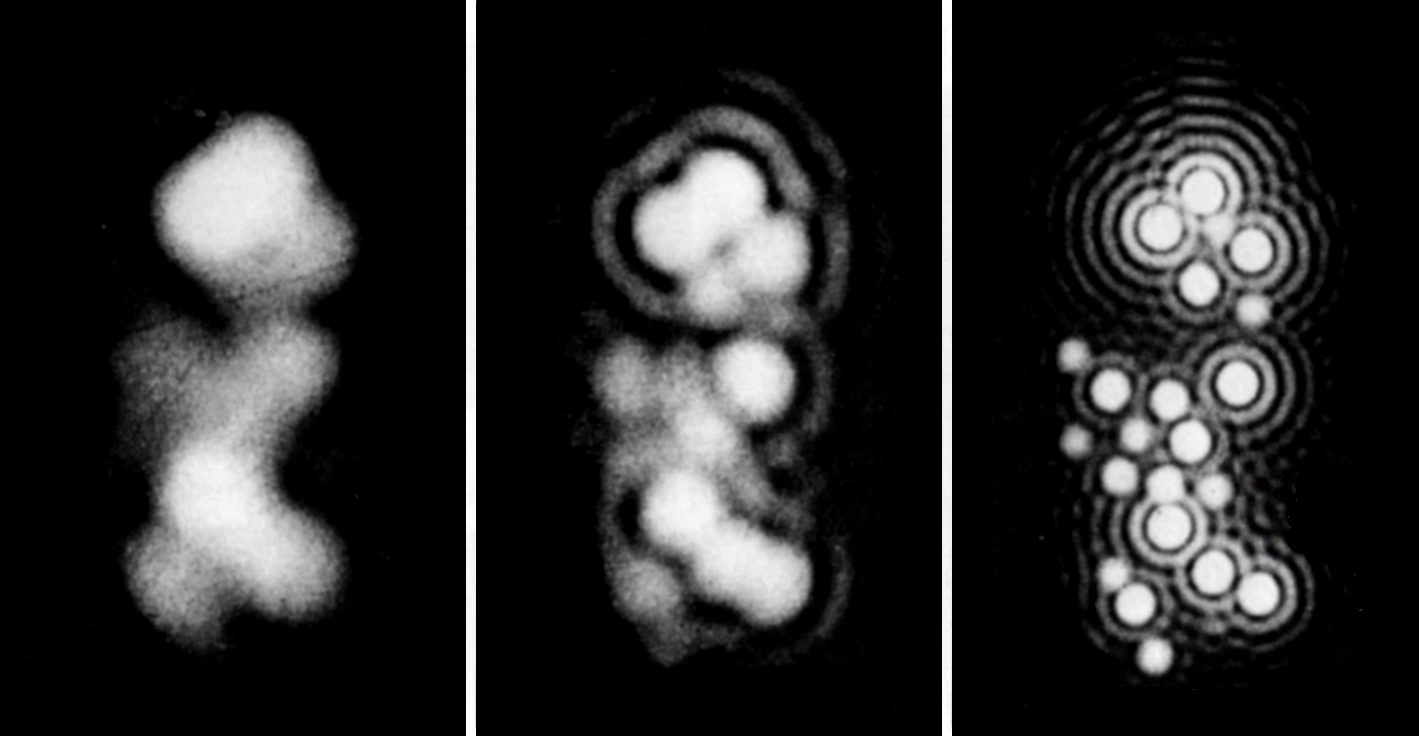

In figure 3 you can see a difference in resolution between an ordinary 10X/0.25 and a highly corrected, so-called apochromatic 10X/0.40 microscope objective. In figure 4 you can see a similar comparison, but between 20X/0.40 and 20X/0.75 objectives. In both examples, you can see that by increasing our numerical aperture, we get a higher resolution. This relationship is linear: by doubling our numerical aperture, we also double our resolving power. Higher NA objectives also capture more light but, in this case, the relation is often not linear. This is because highly corrected objectives also have much more lens elements and the more glass you put in an objective, the more of the light is absorbed by that glass.

Fig. 3: A direct comparison at 10x magnification. Left: image from a standard 10x objective with a 0.25 NA. Right: image from a 10x objective with a higher 0.40 NA. Notice how the higher NA image on the right is significantly sharper and resolves fine details that are completely blurred in the image on the left.

Fig. 4: The same principle shown at 20x magnification. Left: image from a 20x objective with a 0.40 NA. Right: image from a 20x objective with a much higher 0.75 NA. Here, the difference is even more dramatic. The higher NA objective on the right reveals a level of detail and clarity that is completely lost in the lower NA image.

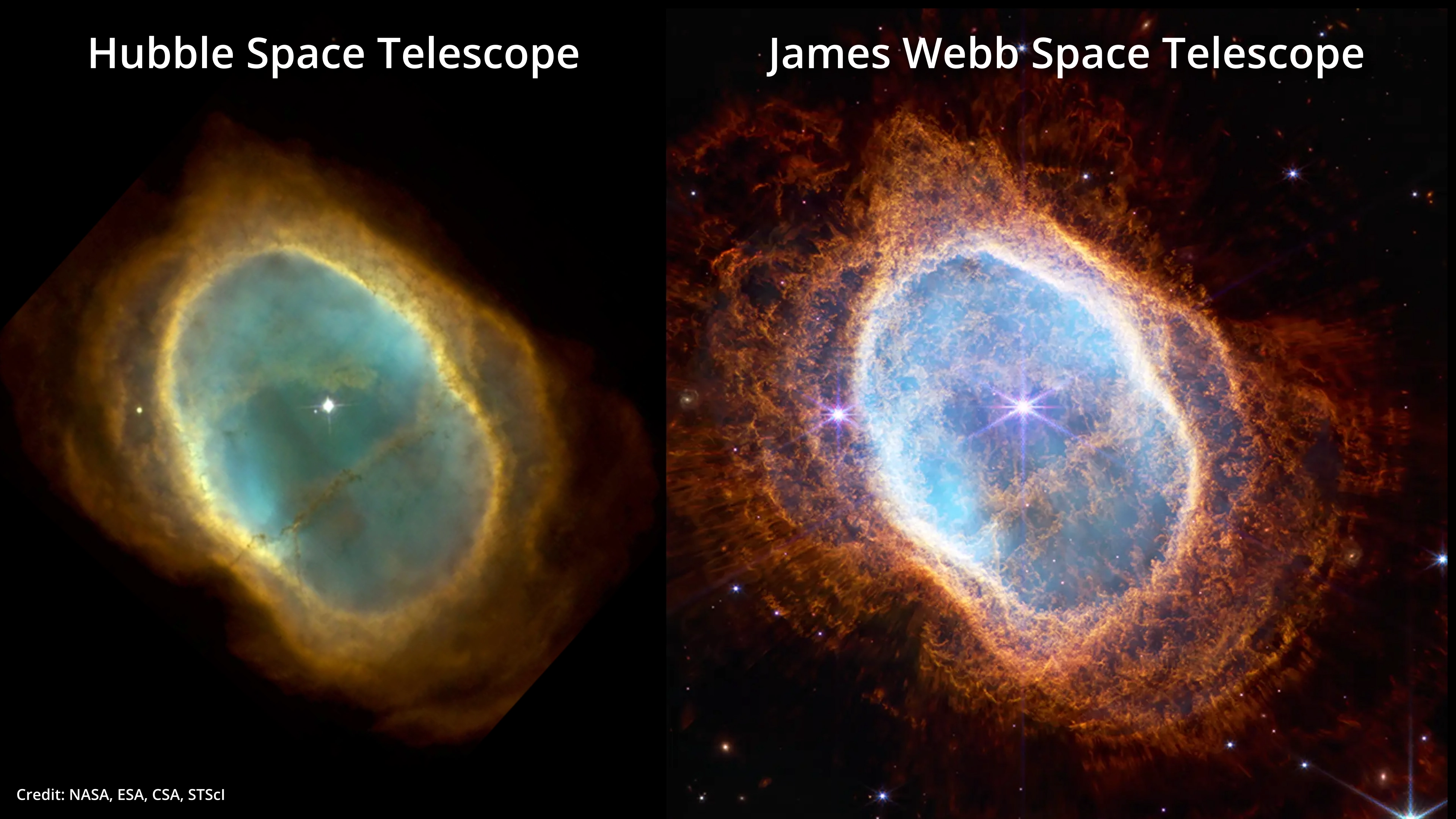

The same rules apply to other fields, not just microscopy. This is why in astronomy, for example, there is a push for ever larger space telescopes. In figure 5 you can see a difference in image resolution between the Hubble Space Telescope launched in 1990 and the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Compared to Hubble's 2.4m mirror, JWST’s 6.5m mirror is capable of resolving much smaller objects, despite the fact it works in the infrared spectrum and can detect only longer wavelengths. Another good example from astronomy is the Event Horizon Telescope which was used to capture the first image of a black hole in 2019. That was accomplished with a global network of radio telescopes and combining them to “artificially” create an earth-sized aperture.

Fig. 5: The principle of aperture and resolution, demonstrated in astronomy. Left: The Southern Ring Nebula imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope (2.4m primary mirror). Right: the same object imaged by the James Webb Space Telescope (6.5m primary mirror). Just as with a high-NA objective, JWST's significantly larger mirror (its "aperture") allows it to gather more light and information. This results in a dramatic increase in resolution.

If this was a scientific publication, our job of explaining the relation between numerical aperture and resolution would be quite easy, as we would only need to write one mathematical formula:

Resolution (r) = λ/(2NA)

Where NA is the numerical aperture and λ is the imaging wavelength.

Unfortunately, this is not a scientific publication and that means we need to do the hard work of actually explaining why a higher numerical aperture gives higher resolution.

Let’s begin with light. Light is a wave. You’ve probably heard that light is also a particle, but no it isn’t...at least not in our oversimplified story. In our case, it is just a wave with a fixed wavelength. Also, the fact that light is a wave means that light is not traveling in straight lines, but, well, as a wave.

So, let’s now take as an example that we are imagining a single-point source or a really small object. Light from that object is traveling in all directions but, with a microscope objective, we are collecting only a small portion of that light. How much light (information) we’ll collect depends on the numerical aperture of the microscope objective. For now, it is only important to remember that higher NA objectives will collect a bigger portion of that light or “more information”. We’ll later get to an explanation of why that is important.

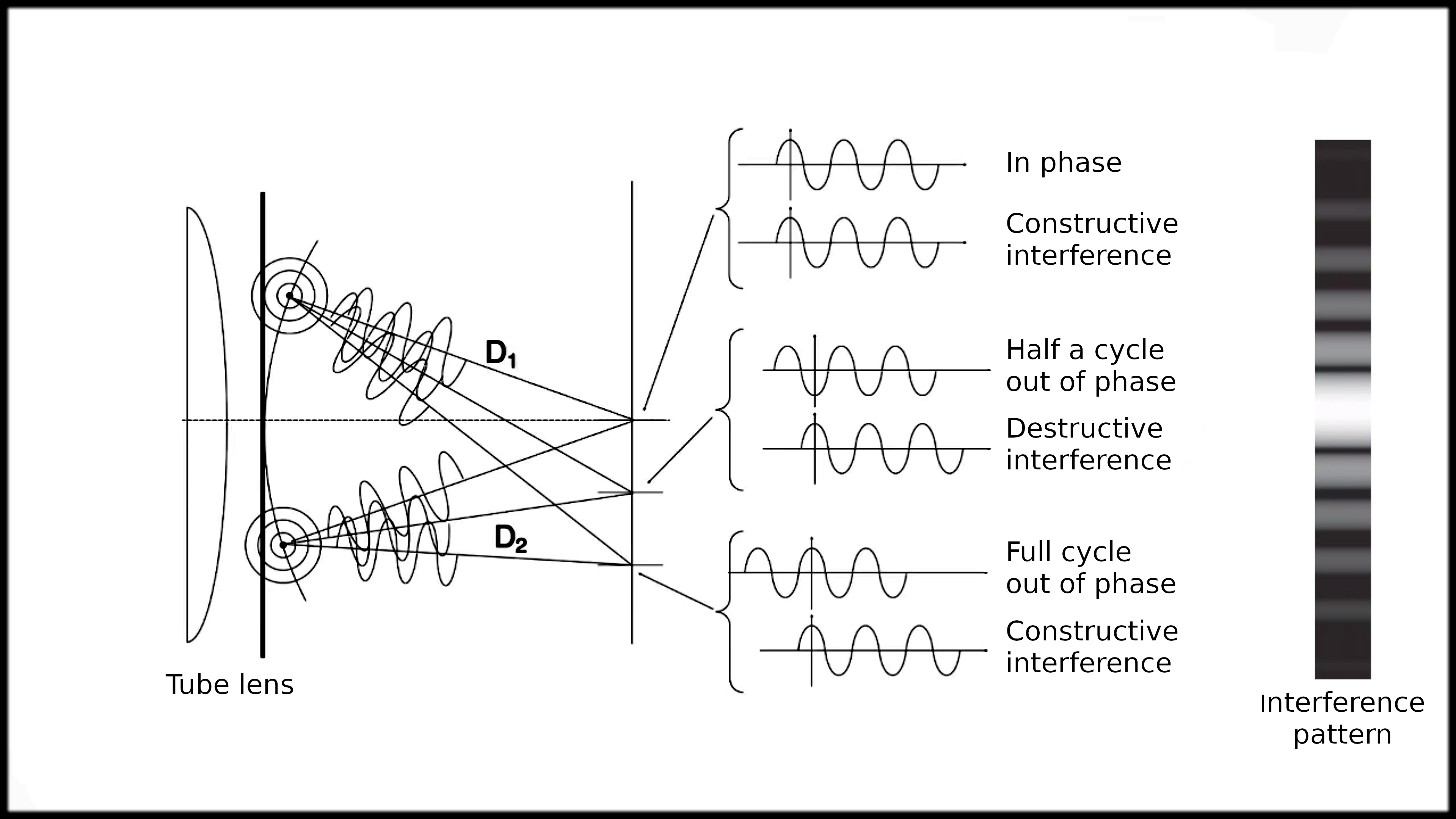

Every microscope objective, regardless of its NA, will then focus that light on a camera sensor or an eyepiece. Because light is a wave, focusing will produce a pattern of constructive and destructive interference as shown in figures 6 and 7. In our example, we are focusing that light on a monochrome (black and white) camera sensor and producing a pattern of white (constructive interference) and black (destructive interference) circles. This pattern is called an airy disk. It is always produced by an objective lens, but in microscopy, we don’t see it often because we are rarely looking at single, small objects. In astronomy that is done much more often and this is why airy discs were first described by astronomer George Biddell Airy who saw this pattern around stars.

Fig. 6: This diagram illustrates how a lens creates an image from interference. When waves arrive in phase, they add together to create a bright spot (constructive interference). When waves arrive half a cycle out of phase, they cancel each other out, creating a dark spot (destructive interference). This final "interference pattern" of bright and dark spots is what forms the image at the focal plane.

Credit: Jeff Lichtman

Fig. 7: This image illustrates the link between NA, the Airy disk, and resolution. We are looking at the same cluster of point-like objects imaged with three different numerical apertures. Left (Low NA): With a low NA, the Airy disk produced by each point is very large. They overlap so much that they blur together into a single, unresolved blob. Middle (Medium NA): As the NA increases, the Airy disks become smaller, and we can start to distinguish the individual points. Right (High NA): With a high NA, the Airy disks are very small and tight. Each point source is clearly "resolved" as a separate entity, revealing the true structure of the cluster.

Credit: M. Francon (Progress in Microscopy)

So, a single point source from a specimen will always produce a specific pattern, an airy disk when focused due to constructive and destructive interferences between light waves. That pattern won’t always be the same though. Higher NA objectives (and shorter wavelengths) will, due to interference, actually produce a “sharper” pattern, and in the end higher resolution images. That’s why numerical aperture is so important.

Finally, here is a short simulation that perfectly demonstrates the effect of numerical aperture on the final image. You can see how a higher NA objective is able to capture more information (the wider diffraction patterns), which is what allows it to create a sharper, more resolved image.